General American English Consonants

General American English Consonants

With accent learning, it is important to work on General American English consonants in addition to vowels. There is so much to think about with consonants in American English, that it requires its own blog post 🙂

General American English Consonants

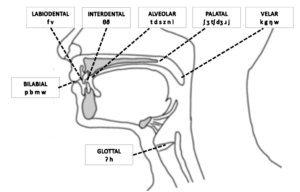

In General American English (GenAm), we have 24 consonant sounds. Consonants are categorized by place, manner, and voicing.

- Place: refers to the articulators that work together to produce a sound. For example, /p, b/ are considered bilabials, meaning they are produced using your top and bottom lip, and /f, v/ are considered labiodental, meaning they are produced using your bottom lip and top teeth.

- Manner: refers to how the air flows through the articulators. For example, /p, b/ are considered ‘stops,’ meaning that airflow is completely blocked by the lips, and /f, v/ are considered ‘fricatives,’ meaning that airflow is partially blocked by the lower lip and upper teeth.

- Voicing: refers to the activity of the vocal folds in the voice box. When the vocal folds are apart and not vibrating, the sound is voiceless (p, f). When the vocal folds are together and vibrating, the sound is voiced (b,v).

Chart

The picture below is a good example of where sounds are produced in the mouth.

See the Manner Place and Voicing Chart for more detail and GenAm examples.

Common Patterns

Consonants can occur in 3 positions of words.

- Initial, beginning of words, like /f/ in ‘fish’

- Medial, middle of words, like /f/ in ‘muffin’

- Final, end of words, like /f/ in ‘puff’

Languages have different rules for what sounds can occur in positions. For example, in GenAm, we do not have ‘ng’ in the initial part of words but we have it in the medial and final positions (e.g., singer, ring).

Languages also differ by their phonological repertoires, or the inventory of speech sounds. For example, Spanish doesn’t have the /z/ sound as in ‘zoo’ and Mandarin does not have blends like the /sl/ in ‘slide.’ English consonants that are considered uncommon in other languages:

| Consonants: | Typical Substitution: |

| Voiced and voiceless ‘th’ /ð, θ/ as in ‘the’ and ‘think’ | t, d, f |

| /z/ as in ‘zoo’ | s |

| ‘dg’ /dʒ/ as in ‘jump’ | ‘zh’ or ‘y’ |

| American ‘r’ /ɹ/ as in ‘red’ | flapped or trilled r |

Common Patterns

While you will usually address subtle differences in sound production, such as more/less aspiration or a slight change in tongue position, here are common patterns noted in accent modification:

| Pattern | Description | Example |

| Devoicing of sounds | substituting a voiceless sound for a voiced sound | ‘to’ for ‘do’ |

| Voicing of sounds | substituting a voiced sound for a voiceless sound | ‘do’ for ‘to’ |

| Deletion of final consonants (DFC) | deleting sounds at the end of words | ‘baugh for ‘ball’ |

| Epenthesis | adding a schwa or ‘uh’ in words in initial, medial, or final positions as well as in blends | ‘suhlide’ for ‘slide’ |

| Substitutions | substituting one sound for another, especially if the sound is not in the client’s L1 | ‘night’ for ‘light’ |

| Distortions or approximations | producing the sound incorrectly | producing /s/ with a frontal distortion or lisp |

‘R’ and ‘L’

A quick note about the two most difficult sounds to produce in English, the ‘R’ and ‘L’:

‘R’

/ɹ/ can be the most difficult sound to produce for both native and non-native speakers because there are no oral landmarks. In all other consonants in English, the articulators make contact with each other. For /ɹ/, the tongue is just hanging out in the oral cavity. Some languages don’t have this sound (even if they think they do), or it is produced as flapped, with the tongue tip behind the alveolar ridge like a /d/ sound or trilled, like the rolled ‘R’ in Spanish.

Additionally, there are two ways to produce the GenAm /ɹ/- bunched vs retroflex. These are just what they sound like. For the bunched /ɹ/, the tongue is pulled back, or bunched up, with the sides close to the top teeth. Some people use the image of a mountain. For the retroflex /ɹ/, the tongue tip is curled up and backward like a ‘C.’

Lastly, vocalic /ɹ/, which refers to any /ɹ/ that follows a vowel-like -er, air, or, takes on vocalic properties depending on what vowel comes before it. Typically -er, as in ‘earth,’ is the most difficult, especially the blend –erl as in ‘girl, world.’ So, this means there are many types of /ɹ/ productions to learn.

‘L’

While /l/ does have oral landmarks, it can be difficult to hear in words, especially in medial and final positions. Brains just fill in the blanks with what they think they heard, which is why errors typically occur more in the medial and final position of words than initial position. This sound can be colored by vowels as well, just like vocalic /ɹ/. Additionally, some languages interchange r/l without changing the meaning of the word.

For words that contain /ɹ/ and /l/ blends, such as “slide” or “broom,” it’s best to first address these sounds individually in the initial, medial, and final position of words before having the client practice them in blends.

Choosing Consonant Targets

Some accent modification clients will only have a few consonants to address, but others will have many. To prioritize goals, consider the following:

- Sounds that do not occur in the client’s native language/s

- The frequency the sounds that occur in English

Ex. /s/ is more common than /ʒ/ - Impact on intelligibility or speaker’s ability to be understood

Keep in mind that languages have different rules for sound production, so even if a sound occurs in the client’s native language, the production may be different. You may find yourself working on subtle differences, such as more/less aspiration or a slight change in tongue placement. Ex. Hindi speakers may use a retroflex /t/

Articulation Hierarchy

A systematic way to address segmentals is to use the traditional articulation hierarchy. In this hierarchy, sounds are addressed in the following order:

- Isolation and/or syllables

- Initial, medial, final positions of wordsAll positions of words in:

- Phrases

- Sentences

- Short reading passages (2-4 sentences)

- Long reading passages (5+ sentences)

- Short spontaneous speech (1-3 sentences)

- Long spontaneous speech (3-5 minutes)

Initially, sounds should be introduced individually, in one-word position (initial, medial, or final) and in 1 syllable words. As the client makes progress, you can quickly increase word length to 2-3 syllables, introduce other word positions, as well as target more than one sound in each trial.

You can read more about the traditional articulation hierarchy in my blog on Articulation Therapy.

As I mentioned earlier, accent modification is more than just sounds. You need to work on how sounds are produced in words as well as phrases and sentences because sounds are influenced by the other sounds that come before and after it. This is called coarticulation. For example /t/ in the word ‘that’ changes in the following ways:

- Single word ‘that’ the /t/ is a hard, aspirated sound

- Phrase ‘that dog’ the /t/ becomes dropped for the /d/ sound

- Phrase ‘that one’ the /t/ becomes a glottal stop

Consonant Resources

There are lots of resources online for consonant stimuli. For elicitation techniques for all consonants and vowels in General American English (GenAm), click here!

A few recommended websites for consonant word lists that are adult-friendly (no pictures) are:

a. Tools for Clear Speech: https://tfcs.baruch.cuny.edu/consonants-vowels/

b. Home Speech Home Word Lists: https://www.home-speech-home.com/speech-therapy-word-lists.html

3 Comments